"Berang" (berang)

"Berang" (berang)

10/29/2015 at 23:01 • Filed to: trojan utility car, 2-stroke, engine design

17

17

7

7

"Berang" (berang)

"Berang" (berang)

10/29/2015 at 23:01 • Filed to: trojan utility car, 2-stroke, engine design |  17 17

|  7 7 |

If you’re the sort of mechanism-oriented car enthusiast that I am, you instantly give respect to any machine that has an engine out of the ordinary; Whether it is something so simple as horizontally opposed cylinders, or air cooling, or something more exotic such as a rotary or sleeve valve engine. You’re probably aware of those cars that had them. But are you aware of the Trojan Utility Car’s strange “duplex” 2-stroke?

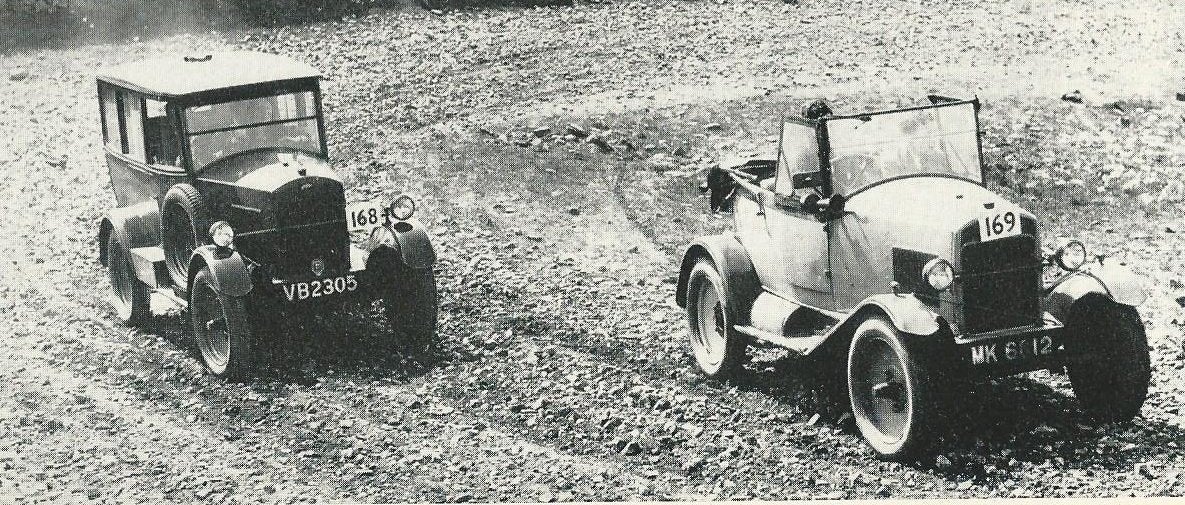

First let’s introduce the Trojan car. Outwardly it was a fairly ordinary looking machine for a 1920s automobile. But like that shy, silent girl who’s secretly a massive pervert with a stash of yaoi doujins - looks were deceiving. On the inside the Trojan was anything but orthodox. For one you might have expected the engine to be under the front hood. But it’s not. It lives under the front seat. The carburetor though lives under the front hood along with the gas tank and the radiator. The transmission was a two speed epicyclic unit not too unlike those fitted to the Ford Model T. The car didn’t have a frame in the traditional sense, the chassis was essentially a deep metal tray which held all the machinery, and on top of which was bolted the body.

But the engine was the masterpiece of this amalgamation of odd features.

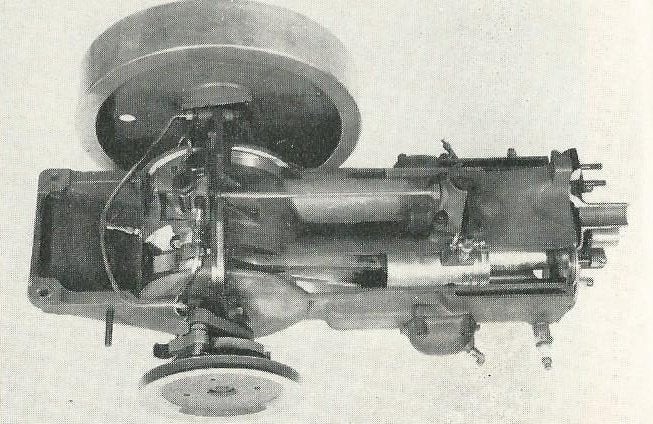

It was a 2-stroke design with four cylinders arranged in a square formation. Four pistons, but only two connecting rods and two combustion chambers. Each pair of cylinders shared a common combustion chamber and each pair of pistons shared a Y shaped connecting rod. And this, as weird as it sounds, was actually quite brilliant.

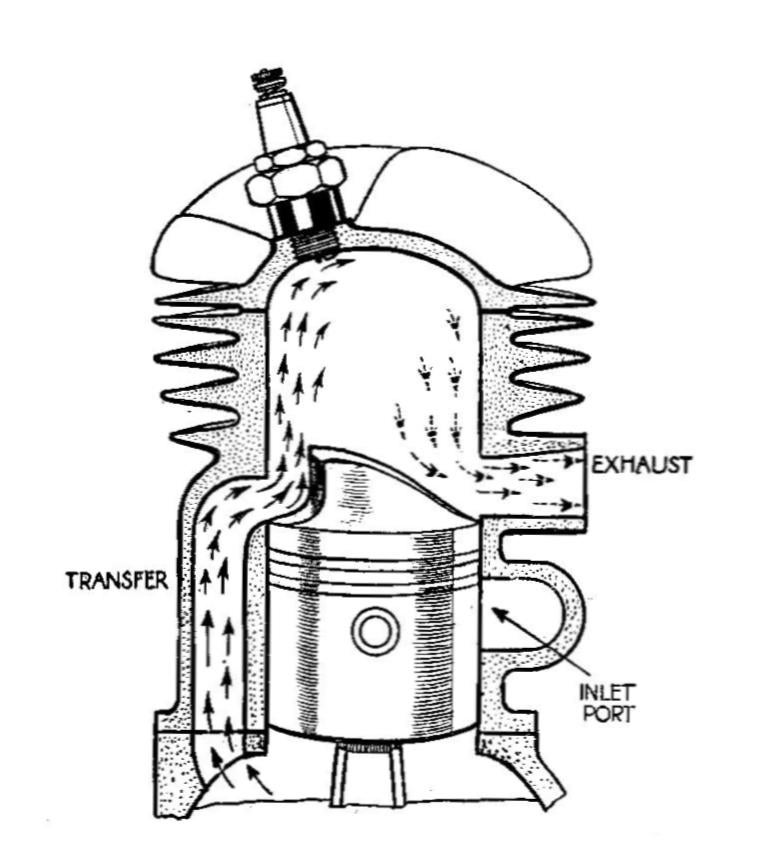

Prior to the invention of Schnuerle porting, 2-stroke engines mostly relied on a deflector piston to achieve adequate scavenging. Additionally, expansion chambers were not in general use (and where they were, they were poorly designed, as exactly how to make them work well wasn’t understood until decades later) and 2-stroke engines suffered from breathing problems.

The Trojan’s engine provided a solution - the heavy deflector piston could be ditched, and proper scavenging could be achieved if the cylinders shared a common combustion chamber. Instead of using a fin on the top of the piston to send the fresh charge up to the top of the combustion chamber, one cylinder would have the intake port, and the other cylinder would have the exhaust. The intake charge would first fill the intake cylinder, pass through the combustion chamber, and then pass down into the exhaust cylinder, effectively clearing exhaust gasses without the need for a deflector fin on the pistons. If you can’t quite wrap your head around the process, this illustration of a later Puch variation on the theme should make it more clear:

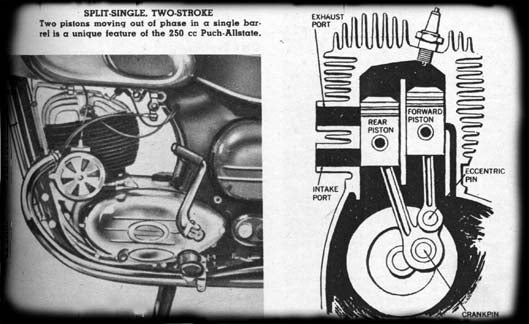

The intake charge goes into the the intake cylinder, up over the cylinder wall, then down and into the exhaust cylinder, effectively scavenging the cylinders. One odd thing about the layout as used by the Trojan was that unlike Puch’s later “twingle” the Trojan used a one-piece Y shaped con rod. Doing so meant the con rod had to bend slightly every revolution, and it was engineered to be slightly springy to do just that. Leslie Hounsfield who designed the car pointed out that this was more “mechanically correct” than using a two-piece con rod like Puch later did.

The second advantage this layout provided was that port timing could be manipulated easier. Since the intake port and exhaust ports were located in different cylinders, and covered and uncovered by different pistons there was a little bit more flexibility to be had over typical 2-stroke designs of the era. The intake port could open sooner, and the exhaust port could stay open longer than in an engine with a deflector piston. The result was that a very flat torque curve was obtained. Nearly maximum torque was available right off of idle and the engine could be lugged in a way modern 2-strokes can’t be.

For some years this sort of “duplex” engine was popular, particularly in motorbikes where it was often refered to as a split single, or “twingle” engine. The adoption of Schneurle porting largely killed off the type, although a few makers such as Puch continued building through the 1960s. The revolution in expansion chamber design that happened in the 1960s was the final nail in the coffin.

Getting back to the Trojan - There’s more! Everything else you need to know about the car (except the bit about it being cheaper than walking) is summed up in this silent promotional movie:

dogisbadob

> Berang

dogisbadob

> Berang

10/29/2015 at 23:09 |

|

Nice writeup.

BJ

> Berang

BJ

> Berang

10/29/2015 at 23:09 |

|

Fascinating. Thanks for sharing this.

Spoon II

> Berang

Spoon II

> Berang

10/29/2015 at 23:16 |

|

That’s fascinating! Thanks for the article!

Speed

> Berang

Speed

> Berang

10/30/2015 at 06:50 |

|

Very cool! I’m always looking for oddball engine configurations and hadn’t seen this. Bookmarked! Thanks!

Jonee

> Berang

Jonee

> Berang

11/11/2015 at 00:04 |

|

Interesting. I was familiar was this car, but didn’t know all the engine details. The original Iso Isettas used a twingle that was apparently very problematic. Why, I’m not sure.

Berang

> Jonee

Berang

> Jonee

11/11/2015 at 01:35 |

|

Yeah it’s a weird one, adding to the strangeness the prototype was developed many years before the car actually went into production. In fact it took 7 years, although WWI was mostly to blame for this. And while I may be misremembering this, I think they were built in the same factory that made the Ner-A-Car motorcycles.

Jonee

> Berang

Jonee

> Berang

11/11/2015 at 03:00 |

|

Ah, very interesting. The Ner-A-Car connection might be why I remember it. That was kind of the end of the “let’s try everything” era right when things began to get standardized.